1. Two level architecture

Obvious, and often confusing, variability polarizes linguists, because it can only partially be formalized. It is therefore preferable to some to use theoretical frameworks to make it disappear; this is achieved most simply by reducing the scientific object to an innate Universal Grammar. However, for those interested in the study of language change, linguistic variation plays an important role and for variational linguistics it is actually the real object of science. Even a second subdiscipline, i.e. linguistics of varieties came up, although these two approaches are not strictly discrete (see Sinner 2014, 11-17); indeed, one can to some degree identify complementary avenues of study among these differing research traditions (exemplified by the works of William Labov on one side, and Eugenio Coseriu on the other1 Both expressions have quite different emphases: variational linguistics is decidedly process-oriented; at its core is the formation and spread of variants (or features) and therefore it is more closely concerned with diachrony and empirically attested SPEECH and the biographical context of the SPEAKER in space and time; the linguist who focuses on migration is examining variation, and is in this regard doing variational linguistics.

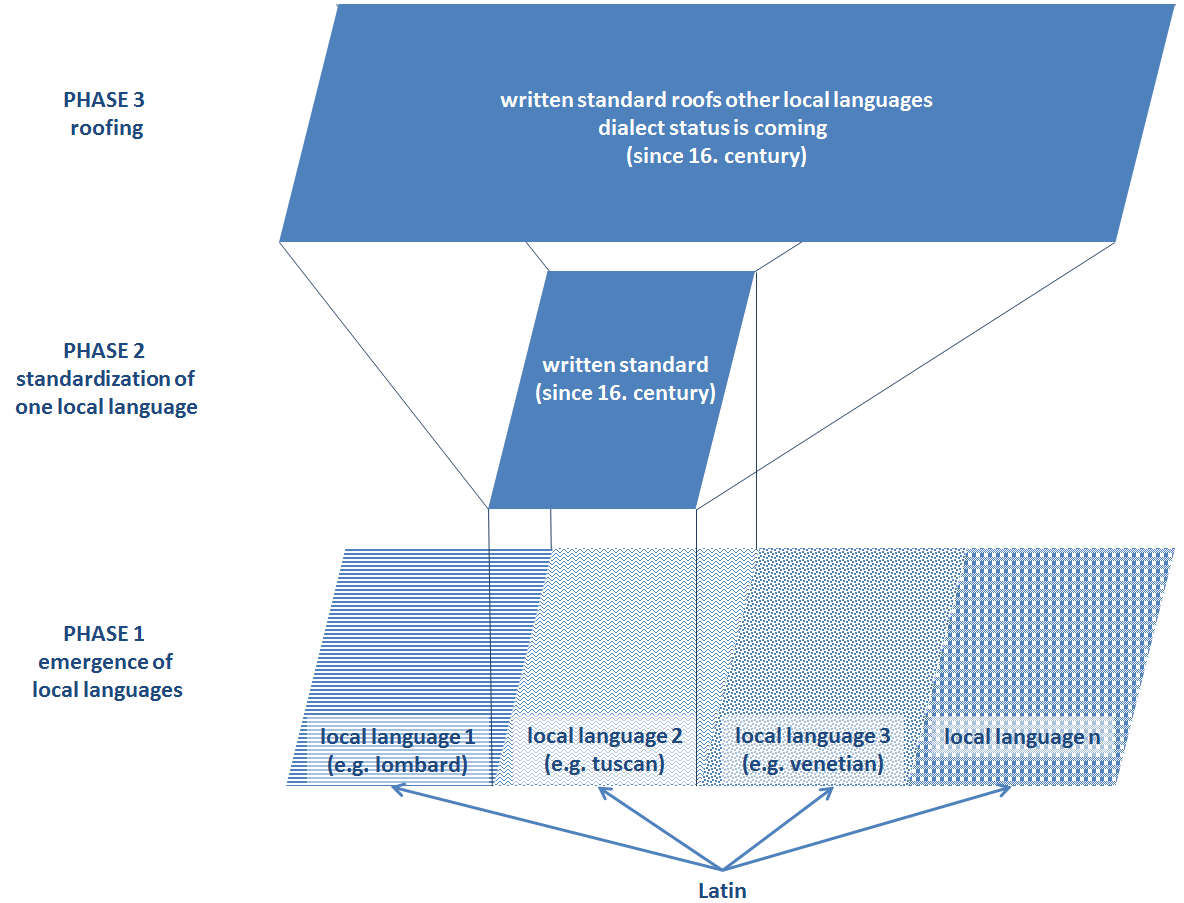

In contrast, variety linguistics is concerned with the aggregation of variants resulting in new varieties. The prime example of a variety is the geographically defined dialect, which can be described as a functioning (i.e. complete and semiotically autonomous) LANGUAGE. The relationship of a dialect as a geographically defined variety to a standard variety (or language) spoken in a larger space and encompassing any number of dialects (for example standard German or Italian) has nothing to do with the emergence of the dialectal forms, but rather represents the socio-linguistic product of historical changes, which determine the system of a local language as a whole and turn it into a dialecte. A dialect is nothing else but a language with an inferior sociological status; it is perceived as non autonomous, because for many comunicative purposes it is replaced by the the standard. Modern languages therefore are said to have a two level architecture with a level of 'basilectal' varieties (or dialects) and a 'roofing' level with a standard variety, also called 'acrolecte'. Žarko Muljačić proposed another very suggestive metaphor when talking of transsatellizzazione of former autonomous Idioms which become ‘satellites’ of a 'sun', that's to say of a standard language, which is building up a sort of gravitational field attracting people to prefer this language to others for the very reason that standard means cultural prestige (see the synthesis in Muljačić 1993, 93. In a very simplified way, the growth of such an architecture (e.g. Italian) might be divided into three phases, as shown in the following figure. Note that the status of dialecte in itself is the direct result of standardization and roofing:

Three phases in the growth of two level language architecture (e.g. Italian)

Furthermore, local dialects themselves reflect their own distinct internal variation, as Louis Gauchat describes in minute detail in his paper on the Franco-Provençal dialect of Charmey – a village in western Switzerland, that at that time (1905) was only reachable on foot. This study could have been groundbreaking, had it received the attention it deserved. Though a complete description of its conclusions cannot be outlined here, it describes a wide variety of sources of variation (using modern terminology) and dimensions of markedness2. His conclusions in brief:

« […] il importe de constater qu’à Charmey, où toutes les conditions sont plutôt favorables à l’unité, la diversité est beaucoup plus forte que je ne me le serais imaginé après une courte visite. […] L’unité du patois de Charmey, après un examen plus attentif, est nulle […] » (Gauchat 1905, 48)

2. Multilingual architecture and challenges of migration linguistics

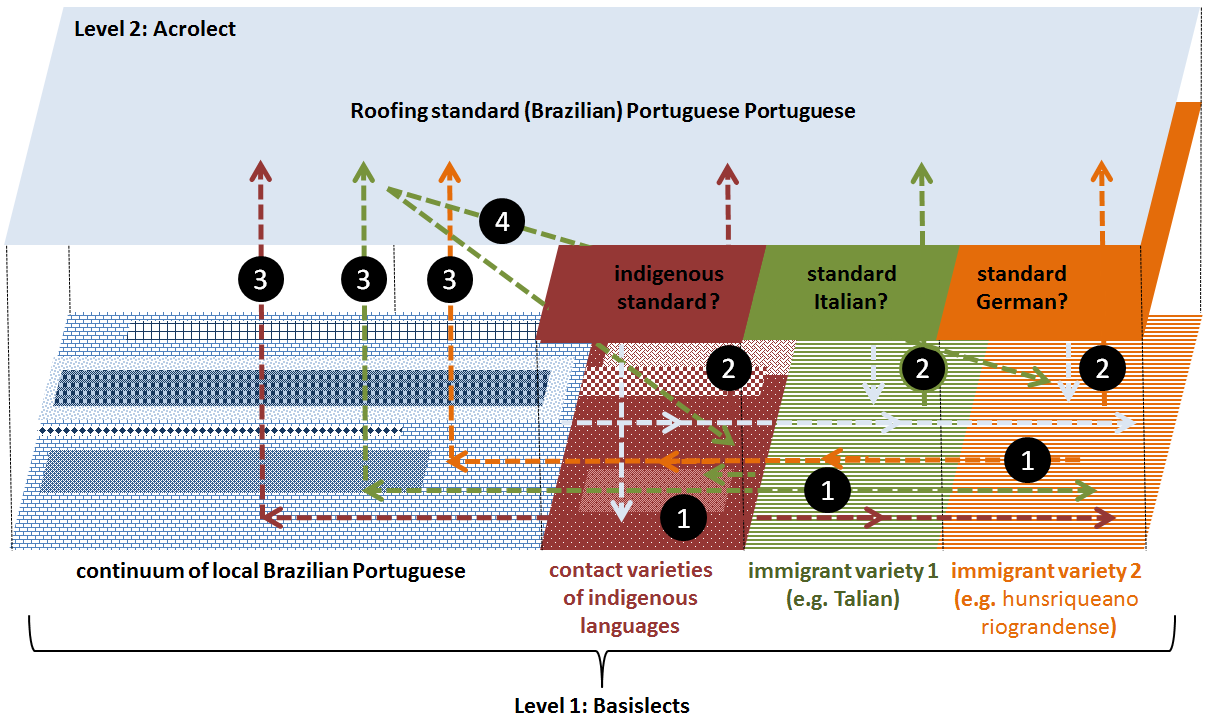

The two level model applies for bilingual or multilingual societies as well. In way a dialect speaker who has a good standard competence is bilingual: otherwise he would not be able to switch between the two varieties. But in this context we want to apply the idea of two level archtitecture for the variation and language dynamics induced by speakers mobility. The question of varieties stemming from migration is of particular interest to the linguist; however, they cannot amply be investigated until the second, or even the third generation. Migration-induced varieties are therefore not spoken by the migrants themselves, but rather by their descendants. They can develop both in the “imported” language spoken by the migrants, and the languages that are regularly spoken in the respective immigration region. These varieties may also outlast the multilingualism whiche stems from migration and characterizes the following generations, such as typical “superstratum effects”, e.g. the multitude of arabic features in Ibero-Romance.

At least, we may distinguish four types of contact variation:

- horizontal borrowing on the basilectal level, form portuguese and/or indegenous brazilian languages to immigrant languages or vice versa;

- vertical borrowing 'from below', from immigrant languages to Brazilian Portuguese standard;

- two sequential borrowings with 2. following 1.;

- tree sequential borrowings, when an element from one migrant language, which reached standard as in 3., is vertically borrowed from above to another immigrant or indegenous language (marked in the figure only in case of Italin origine)..

Multilingual architecture and migration induced variation (e.g. Brazil)

2.1. Suggested application: Talian

In Brazil, the numerous groups of immigrants which partly exist since the 19. century invite for research and especially the use of web technology promises good results. In the case of so called Talian it is easy to compare Brazilian data with data from Italy. A short survey of the situation is given by Ferro 2016 (♦). The following sources are now available for a detailled research in this field:

- the website NavigAIS of the Altlante linguistico dell'Italia e della Svizzera italiana (AIS) can be consulted in the internet;

- a Multimedia Atlas of Veneto Dialects (AMDV), developped by Graziano Tisato, can be downloaded in the internet; it offers a big amount of sound data;

- the family names of the Italians of Rio Grande do Sul may be compared to corresponding names in Italy with the help of the site gens;

- the Italian toponymes in Rio Grande do Sul could be correlated with their correspondents in Italy using the site comuni italiani.